Resources

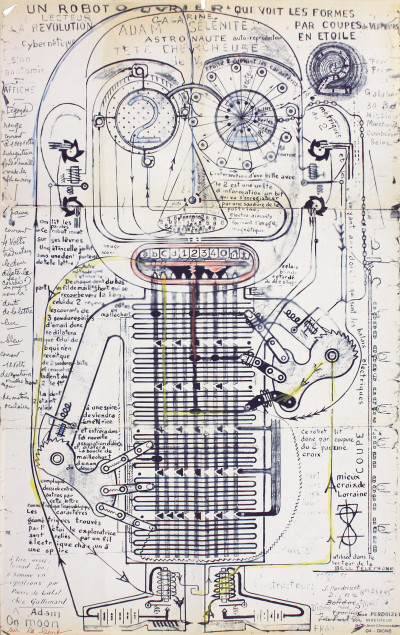

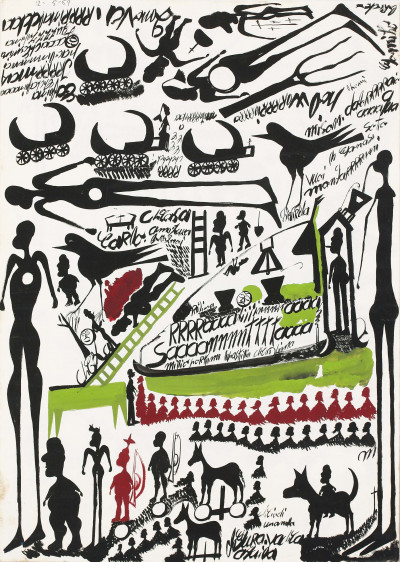

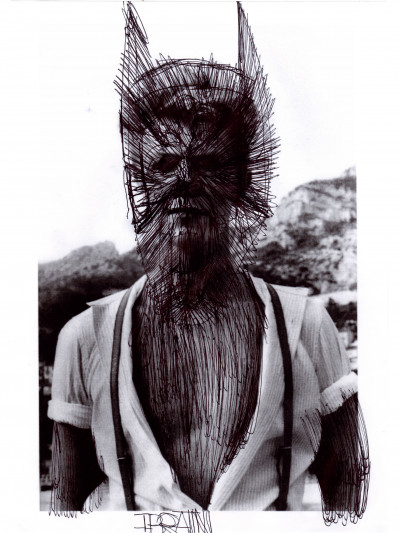

Art brut is above all the expression of individual mythologies produced by personalities who live in otherness—whether psychic or social.

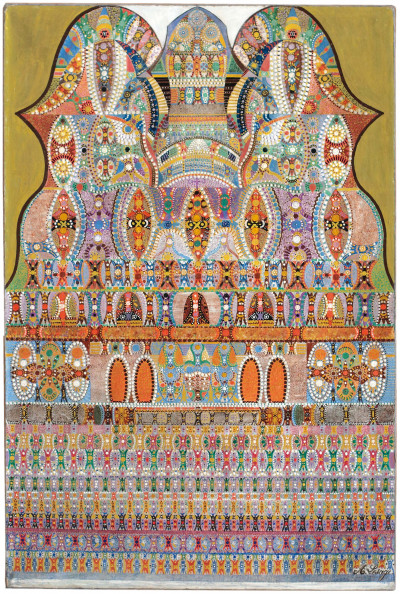

Strangers to the art world, these creators are resistant or even indifferent to cultural norms, and show little concern for the reception or dissemination of their works. Their art often arises from an attempt to elucidate the mystery of being in the world, from a need to repair it, to heal it, to make it habitable. In doing so, it may lead us back to the very origins of art itself.

Christian Berst in 2019

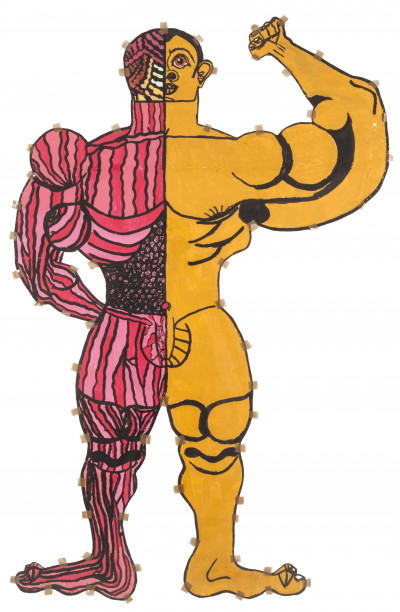

Works of Art Brut are produced by self-taught creators. Art Brut creators – marginal figures, retrenched in positions as spirits rebelling against all norms and collective values and resistant to norms and collective values – include patients interned in psychiatric hospitals, prison inmates, eccentrics, and people living in isolation or rejected by society. They create their works in solitude, secrecy, and silence, with no interest in how they are received by the public or how other people see their work. They have no need for recognition or approval and dream up an imaginary world for their own use – a sort of private theatre that is often deeply mysterious. Their work, often created with unusual media and techniques, is free from the influence of the mainstream artistic tradition, and draws on atypical modes of representation. The concept of Art Brut is thus based on both social and aesthetic characteristics. The term ‘Art Brut’ was coined by the French artist Jean Dubuffet (1901-1985), who was also the driving force behind the study of such art and the original Art Brut collection.

collection de l’art brut, brochure, 2011

« The fact that the definition of Art Brut creators was vague and known only to a small circle meant that it long had a purely discursive status as an object serving Dubuffet’s discourse. » (p.271)

« Dubuffet claimed to be ‘giving a voice to people without culture’, but this was not the case: in fact, he projected his own rebellious, non-conformist intuition onto individuals without a voice. He de-socialised Art Brut creators as a way of studying them in theoretical terms. Dubuffet identified artistic non-conformity with social marginality and cultural exclusion, thereby projecting intentionality onto Art Brut creators, which he was able to do since the social situation of Art Brut creators does not let them turn their own voices into discourse […]. His discourse is likewise a theoretical fiction in this sense: it is invented from a standpoint that does not belong to it. It uses the unoccupied standpoint of another’s voice as a springboard, and again, the search for (artistic) identity draws on alterity. Looking at Art Brut as a theoretical fiction means that we can avoid reducing the paradox to the level of the definition, which would in turn lead to sterile categorisation: saying “this is Art Brut” is meaningless other than to say that Art Brut is nothing more than a collection built up over time – a collection delineated by limits. On the theoretical level, however, the paradox and relevance of Art Brut take on meaning: they draw us into considering the relationship between art and anthropology. »

Céline Delavaux, L’Art Brut, Un Fantasme de peintre, Paris, Palette, 2010. pp 282-283.

[…] I do not entirely subscribe to Dubuffet’s more extreme theories: certain theoretical points — such as the rejection of “cultural” creation and the virginity of Art Brut creators — were advanced in a particular context and no longer possess the same dissident value. Yet two generations after its emergence, Art Brut has retained all of its relevance. Even today, it cannot be ignored because of the disturbing independent power displayed by its creators. Such was the existential and artistic fracture and such were the imaginations of Wolfli, Aloise, and Müller that their encounter with the Other and the Elsewhere retains its radical force. Their symbolic universe plunges us into the heart of an intense and stimulating poetics of the strange.

Lucienne Peiry, Foreword, L’Art brut, Paris, Flammarion, 2001

It has been argued that Art Brut is a phenomenon of the past, that the kind of creators that Dubuffet came across are no more, that today nobody can be unaffected by cultural influences. Although society is changing and television, advertising, pop music, supermarkets, fast food outlets and the like have become standard features of the Western world, their effects on some individuals are superficial. Western society has shown that even in a crowded city, people can be as isolated, and the world can be as hostile and

uncaring as ever.

John Maizels, Raw Creation: Outsider Art and Beyond. London: Phaidon, 2000, p. 226.

Human creativity is a basic urge. […] In certain individuals it will inevitably surface and nothing can stop it. Yet there have been profound changes in both the perceptions and the actualities of non-academic art since Dubuffet first championed Art Brut. Following on from Dubuffet’s reasoning, one might think of Art Brut as the white hot centre—the purest form of creativity. The next in a series of concentric circles would be Outsider Art, including Art Brut and extending beyond it. This circle would in turn overlap with that of folk art, which would then merge into self-taught art, ultimately diffusing into the realms of so-called professional art.

ibid p. 227

Since the name ‘Art Brut creators’ clearly does not suit the myriad of unclassifiable artists to have appeared since the mid-twentieth century, I suggest using expressions that, while doubtless also unsatisfactory to a degree, are nonetheless less restrictive, such as outsiders or artists who are heretical, heterodox, or simply different.

Christian Delacampagne, Outsiders, fous, naïfs et voyants dans la peinture moderne (1880-1960), Paris, Mengès, 1994, p. 132

“Art Brut creators are marginal figures, resistant to educational discipline and cultural conditioning, retrenched in positions as spirits rebelling against all norms and collective values.

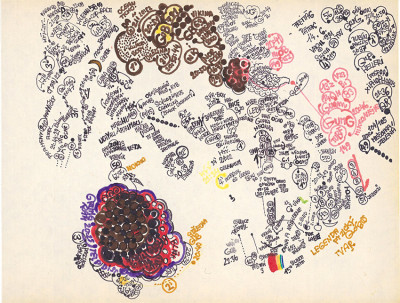

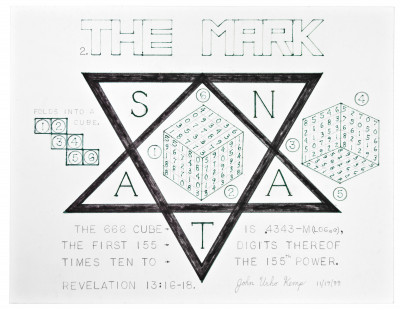

They do not wish to receive anything from culture, nor to give it anything. They do not aspire to communicate, at least not according to the procedures of commerce and advertising inherent in the system by which art is now made available. They are refuseniks and autists in every sense. Art Brut presents corresponding formal traits: their works are largely free from the influence of tradition and artistic context in conception and technique. They use never-before-seen materials, skills, and principles of representation, invented by their creators, and alien to instituted forms of figurative language. In most cases, these social and stylistic characteristics go together and resonate in each other: deviating from the norm encourages unique forms of expression, which in turn heightens the creator’s isolation and autism, so that as he progresses in exploring his imaginary, he withdraws from the cultural field of attraction and norms of mental behaviour.

The author thus thinks of his work as a medium for his hallucinations – and it is indeed a question of insanity, though the term must be stripped of its connotation of pathology. The creative process is triggered as unpredictably as a psychotic episode and follows its own logic, like an invented language. In fact, when Art Brut authors express themselves in writing, they subordinate grammar and spelling to their mental state. It is an impulsive form of creation, often limited in time or sporadic; it obeys no commands, resists all enticements to communicate, and its wellspring may even lie in deliberately failing to meet external expectations.”

Michel Thévoz, Art brut, psychose et médiumnité, Editions de la Différence, Paris, 1990, pp. 34-35.

The origins of the Compagnie de l’Art Brut cannot be understood without reference to the Surrealist movement and there is no overlooking the fact that Breton was himself one of the Compagnie’s founder members […]. Breton could have penned the words in which José Pierre, representing today’s Surrealists, presented the exhibition at the Musée d’Art Moderne, La Fureur Poétique, which is in fact dedicated to ‘André Breton’s spiritual being’: ‘When Jean Dubuffet arbitrarily cut [Art Brut] off from the rest of contemporary artistic activity – which he christened “cultural” – he did a grave disservice to those he was claiming to speak out for. I can’t help thinking about Indian “reservations”, which are hypocritically claimed to protect the survivors of the magnificent American civilisation […] but which in fact are there to stifle them […]. Setting Art Brut against “cultural art” – against the truth, in other words, since there have been a myriad of artists “unscathed by artistic culture”, from Van Gogh to Tanguy – is an attempt to keep a major aspect of contemporary artistic culture in the ghetto by giving it a special status. It should be quite the opposite. Placing Wölfli, Aloyse, Lesage, and Crépin on the same footing as Kandinsky, Miro, Klee, and Matta to prove that the former are echoes, and not poor relations, of the latter is a way of breaking down the dubious barriers of a form of segregation that, like other forms, serves to protect particular interests.

Gaston Ferdière, “A psychopathologist’s point of view”, in Nouvelle revue française, June 1967.

“I want to highlight that I gave the name Art Brut to all productions that are outside cultural art.

There are an infinite number of ways of being outside cultural art. There are an infinite number of artistic stances, of all sorts, covered by the term Art Brut. It is also relevant to observe that every human being is suffused with cultural conditioning and can only partly free themselves from it to a greater or lesser extent. References to cultural conditioning will always remain in any case of Art Brut. This is also true of my own arguments, of course.”

Jean Dubuffet, Letter to Andréas Franzke, 22 October 1980.

Obviously, no-one in the world is completely free from cultural conditioning, which means that no art is totally brut. Art is brut to a greater or lesser extent – it’s a question of degree. And Art Brut has its marginal zones, just as cultural art does, and similarly, you can sometimes find the spirit of Art Brut in works produced by cultural art professionals, breathing new life into their work. It can be very difficult to draw a precise line between what is Art Brut and what isn’t.

Jean Dubuffet, interview with a Swedish radio station, 1980.

Art Brut should be looked at rather as a pole, a wind that blows more or less strongly, and that is usually not the only wind blowing. It is very hard to go against the wind without being blown a little off course.

L’Art Brut, exhibition at the Galerie des Mages, Vence, August-September 1959.

The concept of Art Brut was developed by the artist Jean Dubuffet, best known for his cycle L’Hourloupe, who became interested in the question as early as 1945. He defined Art Brut as works produced by persons unscathed by artistic culture, where mimicry plays little or no part (contrary to the activities of intellectuals). These artists derive everything – subjects, choice of materials, means of transposition, rhythms, styles of writing, etc. – from their own depths, and not from the conventions of classical or fashionable art. We are witness here to a completely pure artistic operation, raw, brut, and entirely reinvented in all of its phases solely by means of the artists’ own impulses. It is thus an art which manifests an unparalleled inventiveness, unlike cultural art, with its chameleon- and monkey-like aspects.

Art Brut prefered to the cultural arts, catalogue of the first exhibition of Art Brut, at the René Drouin Gallery, Paris, 1949.