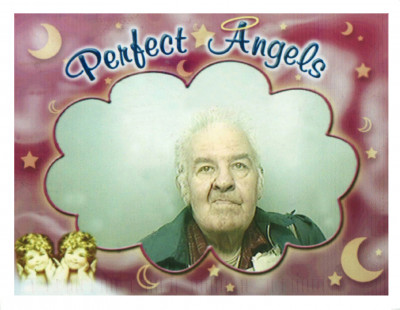

albert moser

life as a panoramic

Just as Miroslav Tichy’s work was met with appreciation by the art world thanks to Harald Szeemann’s exhibitions and, more recently, a retrospective at the Pompidou Center, the work of Albert Moser, a creator as lacking in learning as he is guarded, is a major discovery.

Now that his work is revealed, the eternal question arises again of how such work, designed and stored in secret, should be received. Next, Moser’s creations forcefully pose questions about the problem of photography in outsider art, perhaps even, as André Rouillé writes, “giving the lie to its supposedly manual essential nature.” But over and above the questions concerning criteria and classifications, the work, according to Christian Caujolle, is “comparable to the materialization of a projection of mental images on the world” or even to “a cathartic exercise,” as Phillip March Jones suggests. Besides the poetic audacity, what is striking is the deliberate desire to re-invent, even distort the reality captured in the lens.

Moser cuts his photos and then sticks them together with scotch tape to produce work that breaks with flatness, where the landscape closes in on itself and on the spectator in a sort of optical vertigo that contrasts with the amplitude of the deployment inherent to the wide-angle lens.

Born in 1928 in Trenton, NJ, the autistic son of Russian Jewish immigrants lived with his parents until the age of 60, leaving them only from 1946 to 1948 for the duration of his army service in the US occupying forces in Japan. After that, his life was taken up with a succession of casual jobs and dominated by the idea that he would become a photographer.

Now 84, Moser, who lives in a special home, tirelessly makes hundreds of mandala-like drawings characterized by the scansion of geometric motifs. This ensemble may be the second aspect to his personal cosmology, and its elements, when placed end-to-end, would make up another perfectly imperfect panorama, in the image of life.

This American artist, autistic, lived most of his life with his parents, before joining the New Jersey foster home. Moser first gained recognition for his tinkered photographic panoramas, then for his psychedelic geometric designs. But whatever the medium, his work testifies to the same obsession with space. They report, in their own way, the vertigo through which he tries to find his place in the world. Exhibited in 2019 at the Rencontres de la photographie d’Arles, his work is as well in the collections of Antoine de Galbert (France) and Treger Saint Silvestre (Portugal).