Melvin Way

Gaga City

Melvin Way invented the Dell computer, founded collegiate and educational institutions all over the Northeastern United States, and wrote songs that were recorded and popularized by the Supremes. He had a ticket on the last Amtrak train that crashed near Philadelphia, but missed it, intentionally, because “something just wasn’t right.”

Way’s enormously important intellectual and cultural accomplishments might explain the 6.2 million dollars he made last year. But what would you expect from a man who graduated high school fourteen times (ten times in South Carolina and four times in New York City) and who also happens to be “post-mortal?”

Some of Melvin’s stories don’t quite add up, and private details about a patient’s life can’t be legally disclosed. So, we rely on the artist’s shifting explanations of the past, separating reality from fiction to the best of our ability. Despite some conflicting stories and timeline gaps, it is clear that Way has lived and traveled between South Carolina and New York since he was a child. In the early 1970s, he attended a technical college and played in a music group, composing funk ballads and playing gigs in the city. He also experimented with drugs, and has spent periods of time in and out of various city shelters and programs.

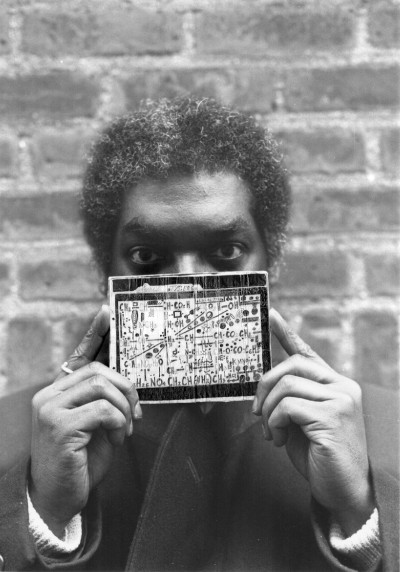

In 1989, Way met Andrew Castrucci, an artist and educator, on Ward’s Island at a workshop run by Hospital Audiences Incorporated (HAI). The program included approximately one hundred men, but Castrucci took special interest in Way’s work. The two formed a friendship and creative relationship that continues today.

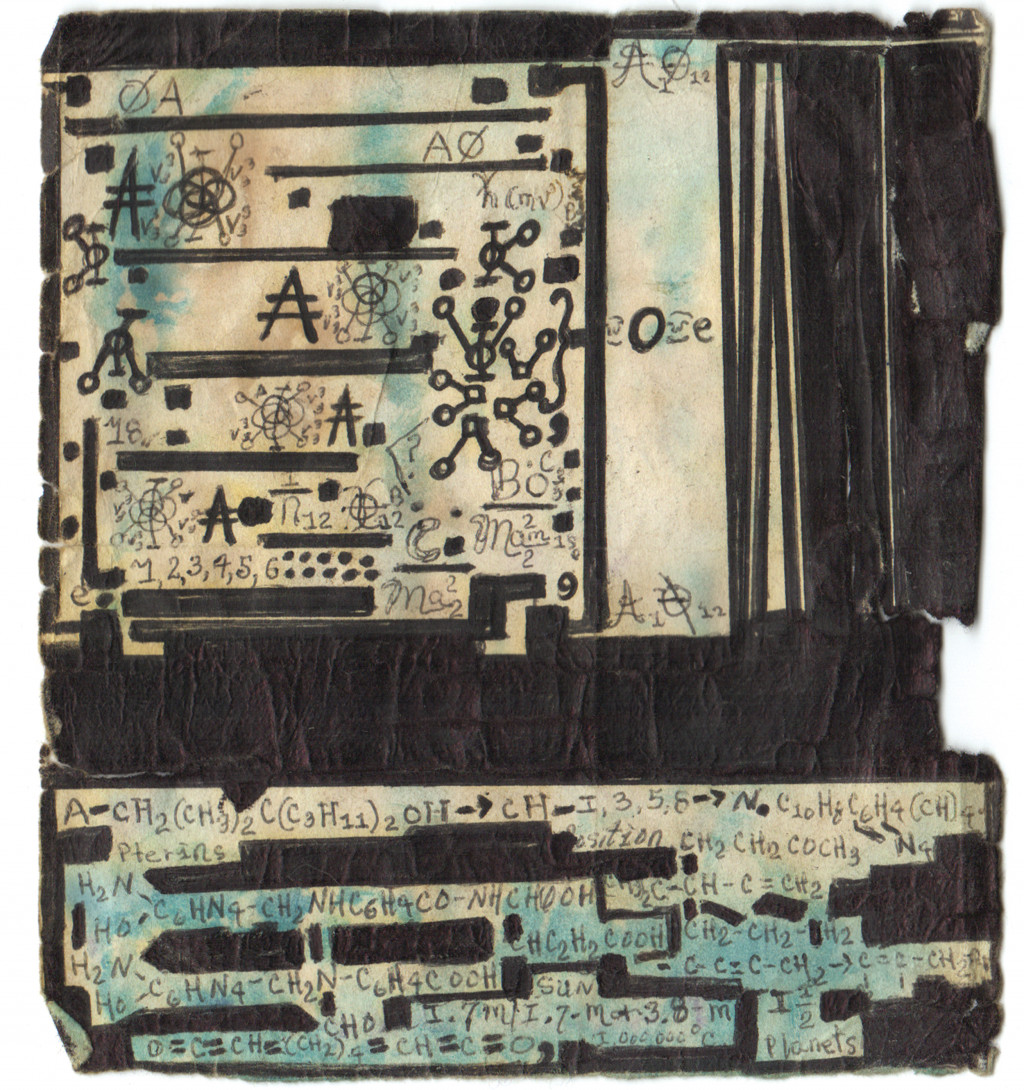

Way’s process is private and portable. He carries his drawings with him for days, weeks, or years, working on them when time or inspiration allows. He draws on found pieces of paper with ballpoint pen, often wrapping his work in Scotch tape—probably to preserve them as they are transferred among books, magazines, pockets, bags, and drawers. Way’s drawings look like copied textbook chemical formulas, but do not ultimately describe any particular substance known to man.

Way’s improvisational and scientific meanderings offer the possibility of a parallel universe—call it Gaga City—where the basic rules that govern our world are displaced, erased, re-drawn, re-configured, and covered in tape. Those new truths are stashed deep in the artist’s pockets or hidden away somewhere for safe-keeping.

Way’s drawings are frequently referred to as “cryptograms,” but by definition, cryptograms can be solved, whereas Way’s drawings have no beginning, end, or decodable message. Instead, they speak to the infinite possibilities of both imagination and science, visually describing other realities and ways of seeing.

Discovered in the early 1980s at a homeless center in New York City, Melvin Way is now a key figure in contemporary art brut. Having interrupted his scientific studies because of his schizophrenia, he relentlessly covered fragments of papers of mathematical and chemical formulas, sibylline sketches… These dense talismanic notes, which he treasured in his pockets, exhaled a rare magnetism. The 2018 Pulitzer Prize for Critics, Jerry Saltz, considers him “a mystic visionary genius, one of the greatest living American artists.” The artist’s works are now in the collections of the MoMA (New York) and the Smithsonian (Washington).

Prefaces : Jay Gorney & Andrew Castrucci

Foreword : Christian Berst

Catalog published to mark the exhibition Melvin Way : gaga city at christian berst art brut, New York, from june, 7th to july 19th, 2015.

OUT OF PRINT