Didier Amblard

Didier Amblard enters the workshop of the psychiatric hospital of Clermont-Ferrand in 2012. There he undertook the project of drawing his former hospice recently destroyed. This ghostly work, with a ballpoint pen, where the silhouettes of those who have disappeared are drawn, seems to become the palimpsest of his environment. Only the sky escapes these metamorphoses and testifies to a possible elsewhere. Represented by the gallery since 2013, his work was presented by Jean-Hubert Martin, in 2016, in the exhibition on the thread, in the exhibition of the Museum of Everything at the Kunsthal of Rotterdam as well as in the Treger-Saint Silvestre collection at the Oliva Creative Factory.

When he was one year old, Didier Amblard, born in 1965 in Nancy, eastern France, moved with his mother, a postal worker, to the Auvergne region in central France. As an apprentice, he worked at a metal factory and then went into building. “One evening, I took it upon myself to draw, in one fell swoop, a train seat, a headrest, a pair of dark glasses like those worn by the singer Dutronc, a monk’s habit and a clove of garlic. My grandparents used to go to the local garlic and chicken fair.” Thus, at the age of 16, his everlasting passion for drawing was discovered. He peddled prints on the Riviera until he fell ill and had to be hospitalized in a psychiatric ward. His son was born in Bar-le-Duc in north eastern France, and there he tried to fulfil his role of father. There too he began dreaming of working as a carpenter and cabinetmaker. He was set to work in a public institution for handicapped persons, where he produced 150 wooden pallets a day and bagged pieces of plastic. One day he broke a saxophone, on another he broke a guitar. He wrote poems and prose filled with words of his own invention, a mixture of aggregates of syllables, grimaces and stutterings.

He continued to draw in his sketchbook and to paint, giving away and distributing his works in the institutions that took him in, but no one showed any interest in them.

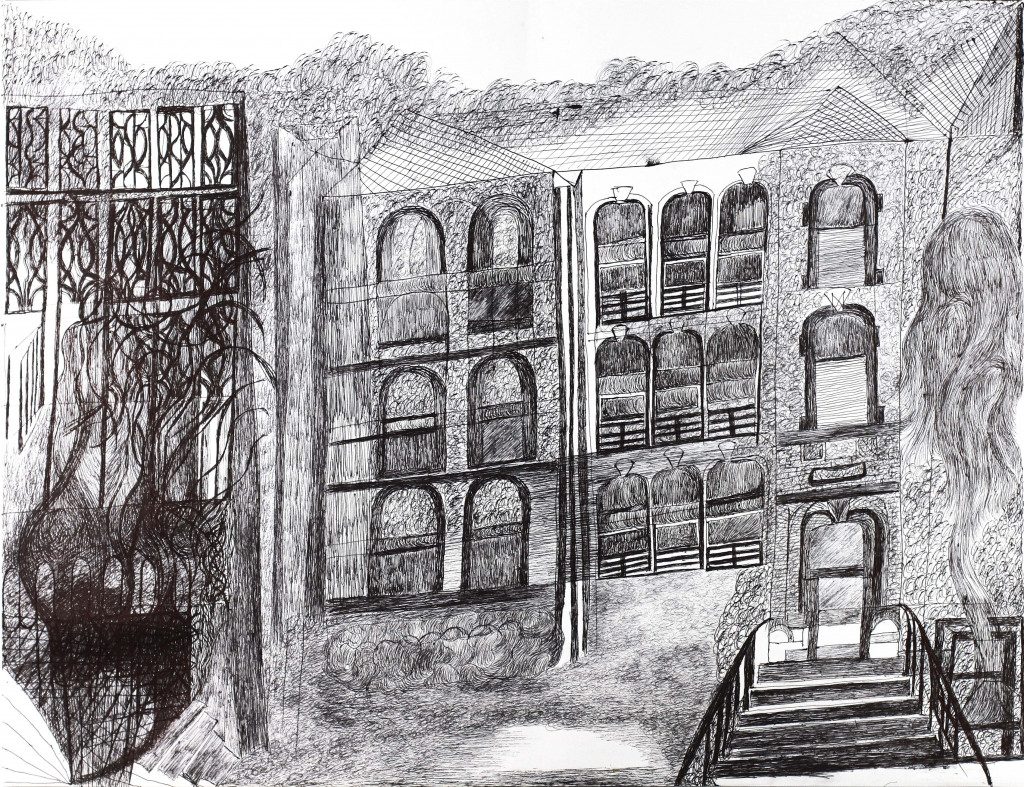

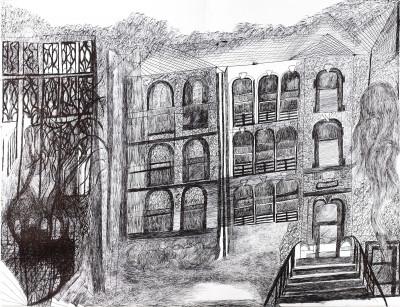

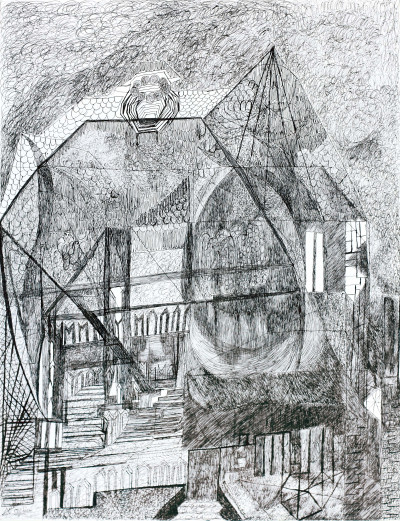

In 2012, Amblard went into the art therapy centre of his hospital. A new hospital was replacing the old one and Amblard, outraged at the destruction of the old chapel inaugurated in 1857, decided to draw his “old hospital”, its outlines and those of his “dead comrades”, those “who could not take care of their children”, those who had headed for disaster and never recovered, wedged into corners pointing towards the sky, “poor cornered souls”, those returning to their “apiary”. He saw their silhouettes behind trees and in roots; they traversed the air, which for him was crowded. He constantly lived in the company of those who “dance seated in their armchairs”. Feverishly, from one ballpoint pen to another, he sought to escape from his disequilibrium, made preparatory sketches of staircases and windows, before he stopped drawing, only to begin again later, until he made his fateful utterance, “I won’t mature it any more.”

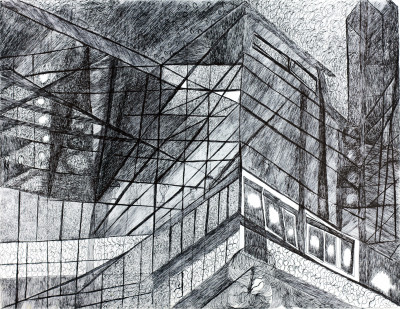

This universe, comprised of the unchanging repetition of ellipses, finishes in a continuum of helicoid representations where the organic and inorganic come together. One of its properties is transparency, the other, ephemerality. From the swirling combination of molecules, worlds in perpetual metamorphosis are drawn out. A few lines give structure, stretching and embedding themselves in the paper as if they were penetrating the skin without penetrating the flesh, gash-like, in a tormented world made of a tangle of nerves and tendons.

Only the sky (in the form of an empty space) is free of these metamorphoses and suggests that somewhere else is possible. All these areas that remain white frighten Amblard: should he fill them? Will that door be swallowed into the ground? Where do the staircases sink in? Both space and time submit to his world.

“My old hospital”, a premonitory anticipation not of future ruins that would enable a belonging to the past (when a building is constructed, should it perhaps be designed according to the ruin it will become?), but rather an anticipation of the disappearance of a chapter of history, that of the mentally ill and the buildings reduced–without distinction–to the role of rubble. “My old hospital” tells a story of the outsiders of Kafka’s village, of the crowd of the unloved, of shapeless shadows, of those walled-up and erased from the collective memory, of the forgotten dead, of those who never came to anything.

Didier Amblard participates in the exhibitions of the art therapy centre as an artist and poet. He is an artist who does not play at being an artist; he forgets his name; he does not sign his work. He has been given a mission that frees him from both social and public recognition.

Preface : Matali Crasset

Foreword : Christian Berst

Catalog published to mark the exhibition Heterotopias : architectural dwellings, from December 9th, 2017 to January 20th, 2018.