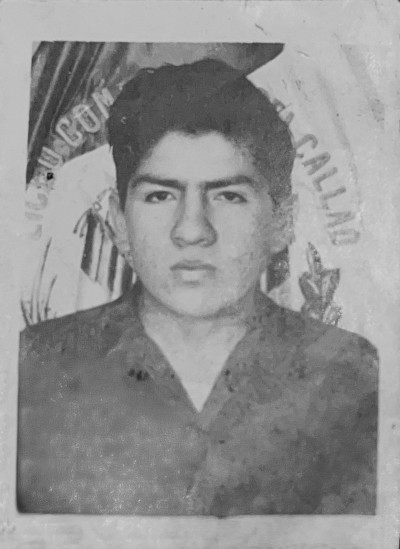

José Gabriel Mendoza Alvarado

José Gabriel Mendoza (1936-2010) was among the last patients whose works the renowned Peruvian psychiatrist Honorio Delgado collected in the 1960s. Originally from the Callao region (Peru), this eldest of eight siblings began showing signs of acute schizophrenia at age 19, shortly after obtaining his accounting degree, which led to his institutionalization for the rest of his life. And it was there that the miracle occurred. In the protective seclusion of the asylum, encouraged by a caring and attentive Professor Delgado, he tirelessly began creating hundreds of feverish and exalted expressionist gouaches.”

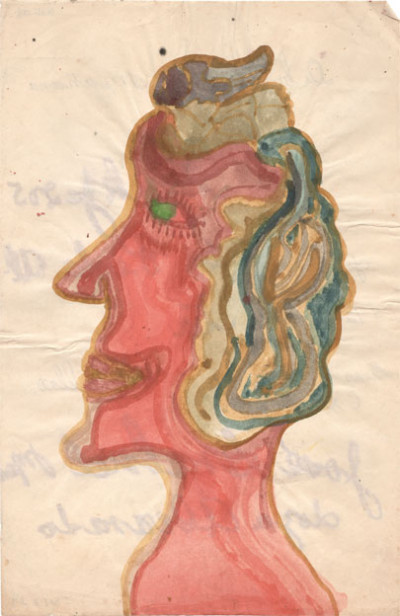

What strikes the viewer at first glance is the blaze of colors, in which bodies and their auras appear intertwined. Then, here and there, something interposes itself—a tree, a cross, a burning bush, a shadow, a chasm. But it is not a backdrop, merely an indication; perhaps a state of mind.

While these presences are asserted with authority, they simultaneously seem to be on the verge of departure, close to dissolution.

If Mendoza’s powerful lyricism is more elusive than that of Nolde and less narrative than Ensor’s, it is likely because he does not aim to shake the society of his time. These works instead appear as traces of a troubled soliloquy, his emotions concealed like apparitions, pulsating and convulsing in unreal shades.

Thus, José Gabriel Mendoza offers us the burning lexicon of his psyche. From the inhabited silence from which he speaks to us, he invites us to look beyond his lament and reaffirm that art is a potent balm that heals all wounds. In this way, the voice of the outcast, the islander, the mute is formed—a precious Palabra del mudo (“The Word of the Mute”), to whom Peruvian writer Julio Ramón Ribeyro lent his pen in a short story collection published in 1972.

Catalogue published for the exhibition

José Gabriel Mendoza: La Palabra del Mudo

from November 14 to December 7, 2024

Texts by: Luz Ascarate & Manuel Anceau

sold out